The xenophobic chicken and the propaganda egg: disentangling official and popular nationalism in China

(Nationalism in China at the moment is a bit cray, part 2)

My article last week on the disgraceful harassment of international journalists in China generated some discussion. Yet in this discussion, as well as in a few other commentaries on these events, I saw a few misunderstandings of nationalism in China today that I wanted to take some time to unpack this week.

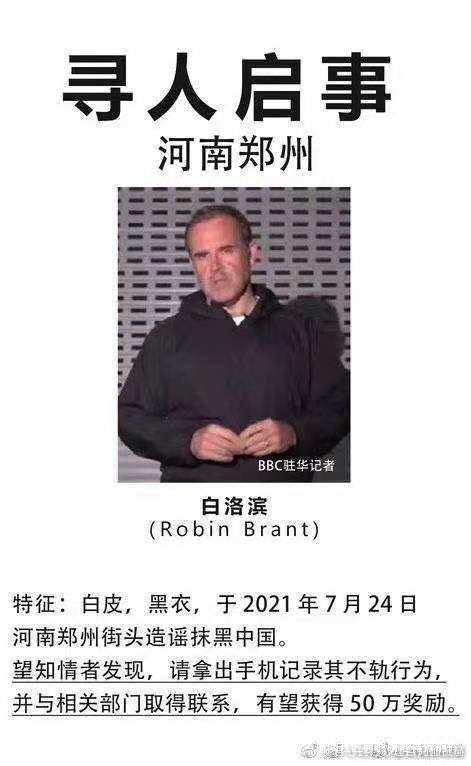

The image above, an imitation wanted ad accusing BBC journalist Robin Brandt of “spreading rumors to defame China,” succinctly captures the at once disturbing and confusing dynamic that I want to highlight: a toxic bottom-up nationalism masquerading as official, while at the same time being intertwined with top-down official nationalism’s targeting of “foreign media,” forming an alliance between the state and the public to displace all anger onto the figure of “the foreigner” so as to forget the system’s many failings.

Misunderstanding #1: the Ministry of State Security controls everything

One respondent on Twitter, with whom I have no beef, commented on my argument about popular nationalism as follows: “‘Nationalism’ as in either MSS/PSB agents wearing plainclothes.”

The theory here seems to be that what looks like ordinary citizens harassing journalists is in fact a pre-planned event orchestrated and directly controlled by the Chinese Communist Party.

Now, I see where this theory comes from, 100%. From the 1999 attack on the US Embassy in Beijing, to the 2005 anti-Japanese riots, to the 2008 anti-CNN silliness, to the 2012 anti-Japanese riots, the Chinese Communist Party does indeed play a decisive role in setting the stage for these moments of concentrated xenophobia. We can see this again in this latest round of xenophobic death threats and harassment in Zhengzhou, where the Communist Youth League and various state media actors such as Guancha have played a thoroughly disgraceful leading role.

Yet at the same time, the Party’s control is not the whole story. It should go without saying that people in China today can make decisions and take actions beyond the direct command of the Party: some such decisions and actions, we must remember, being considerably less laudable than others. To imagine that the people on the streets of Zhengzhou harassing international journalists are taking orders from the Ministry of State Security, or are in fact MSS agents in plainclothes, is not necessarily overestimating the Party’s capabilities, but is certainly greatly underestimating people’s own ability to act in a deplorable manner without direct orders from the Party.

Most dangerously, precisely in attributing acts of xenophobia and harassment to the Party alone, this theory lets members of the general public off the hook for their own actions. We must face the fact such xenophobia is an undeniable trend in popular nationalism in China today: a popular nationalism that certainly grows out of official propaganda, yet which is nevertheless not at all times and in all actions taking direct orders from the Party.

Misunderstanding #2: the misrecognized allure of authenticity

Does that mean that these witch-hunts against foreign journalists are genuine bottom-up initiatives, the authentic voices of “the Chinese people,” which we need to embrace and celebrate for purposes of mutual understanding?

Of course not! No more than Pizzagate should be taken as the authentic voice of “the American people.” Yet some people simply could not resist the temptation of laundering CCP talking points into a seriously cringe-worthy pseudo-intellectual argument.

For example, a certain journalist turned public relations guy, alluding to the events in Zhengzhou, commented on Twitter, “When Chinese people complain about their government, this is an authentic expression of popular sentiment, but when they complain about foreign media, it's because they're mindless tools of propaganda.”

Sigh. Let’s unpack this statement carefully. The author seems to be claiming that (presumably “Western”) readers embrace criticisms of the Chinese government as authentic representations of popular sentiment, while dismissing complaints about “foreign media” as the mindless product of state propaganda.

The reality is that when people in China complain about their government, they do so in direct opposition to years of persistent and all-encompassing state media indoctrination telling them that everything that the government does is great, and that people should be endlessly thankful. They also do so at great personal risk to themselves: speaking frankly about contemporary affairs in China, particularly to “foreign media,” is an act that can result in official interrogation, harassment, imprisonment, and destruction of one’s livelihood. It is, as such, an act that cannot be undertaken lightly.

Understood against this reality, such complaint and criticism does indeed demonstrate considerable courage and authenticity that is worthy of genuine respect.

Meanwhile, when people complain about “foreign media,” they do so on the basis of years of persistent and all-encompassing state media indoctrination telling them that everything that the “foreign media” does is horrible, that this “foreign media” is part of a global campaign to smear China, and that this smear campaign will hinder China’s return to its rightfully glorious place on the world stage. Furthermore, by hindering China’s rise, this smear campaign is imagined to have a direct impact on people’s lives, denying subjects the “dignity” that they want to experience: a dignity that is in fact denied them not by foreigners, but by the Party itself.

What is surprising, then, is not that there are people venting their anger at “foreign media,” but rather that such nasty witch-hunts are not more widespread.

My fear, of course, is that as the current system grows increasingly unstable due to poor decision-making at the top resulting from positive-news-only blinders placed on Chairman Xi, rising dissatisfaction which cannot be directed toward the glorious state without the risk of a lengthy prison sentence will be increasingly displaced onto the sole politically correct target of popular anger: them doggone foreigners!

Misunderstanding #3: the myth of pragmatic official nationalism

One of the defining academic debates on nationalism in China over the past two decades has been the question of whether popular nationalism, cultivated from the top-down by the Party-state, may in turn have a constraining bottom-up effect on official policy, pushing the state through the pressure of public opinion to engage less pragmatically and more confrontationally with the international community.

In the context of the Jiang Zemin or Hu Jintao eras, this was a genuinely ground-breaking and thought-provoking way to look at the relationship between official and popular nationalism. Yet as we shift into the post-Beijing Olympics era and the Xi Jinping era, I propose that it has become increasingly untenable to hold to the idea of an unruly popular nationalism and a more pragmatic official nationalism.

In recent years, the Chinese state has imprisoned and tortured dozens of human rights lawyers who wanted to work within the system to improve the system, imprisoned millions of Uyghurs in concentration camps in occupied East Turkestan, destroyed the foundations of the legal and political systems in occupied Hong Kong in violation of its legal obligations, covered up the spread of a virus that has resulted in millions of deaths worldwide before in turn trying to displace the blame onto other countries, and issued increasingly bellicose threats about invading and occupying its democratic neighbor, the independent nation of Taiwan, for the seemingly unforgivable crime of existing.

These developments, I argue, are not the product of pressure from popular nationalists. In fact, official nationalism, which is in reality a toxic mix of racial essentialism, racism, and personality cult-driven dictatorship increasingly openly resembling fascism, has in recent years become increasingly genuinely terrifying, outstripping in many regards even the most toxic fantasies of popular nationalism (which I researched in my book, The Great Han).

There is, then, no hope of pragmatic official nationalism reining in popular nationalism. And there is of course no hope of popular nationalism reining in official nationalism. There is no longer any self-correcting mechanism in which we can place our hopes.

Rather, I propose that what we saw on the streets of Zhengzhou last week is in fact a disturbing preview of what China’s relationship with the world will look like in the coming years: a self-reproducing cycle of nationalist provocation, attempting at all costs to distract everyone from the very real failings of an anachronistic political system that reliably fails to live up to the needs of an increasingly complex and dynamic society.